No products in the cart.

Spearfishing Advice

How to Spear Fish: The Greatest Spearfishing Guide Ever Created

Before we get stuck into it I just want to say thanks. Thanks for reading this spearfishing guide, thanks for checking out my page, and thanks for your interest in learning how to spear fish. In the following pages I cover everything I’ve learnt from decades in the water, speargun in hand, doing what I love most. Spearing fish. And to make it easy for you to flick through there’s a quick index below covering all the sections in this “How to Spear Fish” guide.

Max Spearfishing is reader-supported. We may earn a small commission for purchases using our links. Click here to learn more.

How to Spear Fish: The Greatest Spearfishing Guide Ever Created

Have a read, and if you’ve got any, ANY questions at all about spearfishing you can email me here.

Right, now let’s get straight into it.

- What do I know about how to spear fish?

- What spearfishing’s all about

- Understand the different types of spearfishing

- How to spear fish and stay safe

- What you need to get started spearfishing

- Rigging your spearfishing gear for your first dive

- Choosing a spearfishing spot

- The importance of proper equalization

- How to actually sneak up on a fish

- Caring for all of this spearfishing equipment

- The benefits of joining a spearfishing community

What do I know about how to spear fish?

Hi. I’m Max. I grew up by a small-town beach in Australia where the beach was the single most exciting thing to do. Every spare minute of my childhood was spent in the water. Mum likes to joke that I could swim before I could walk, and she wasn’t far from the truth. I loved being in the ocean. I also loved eating seafood, but I was never that good at fishing.

Sure, we’d catch a fish or two, but nothing to write home about.

Then one day I came across two guys cleaning two of the biggest jewfish I’ve ever seen. And next to them was a pile of spearfishing gear. They’d speared these monsters, in the same water I’d been playing in my entire life. The fish I’d caught didn’t even come close. These were truly massive.

With wide-eyes I couldn’t help myself. I started asking questions.

- What in the heck kind of fish are those?

- Where do you even catch these things?

- Can you teach me how to spear fish?

- How do their spearguns work and where can I get one?

- What do I need to do to start spearfishing myself?

And probably a hundred more.

I was so keen. And within a few weeks I put together my own spearfishing kit.

Strutting down the beach with an armful of gear, I waded out, geared up and started swimming around the reef along one of the headlands. Fish were everywhere, but they were much too fast for me. I went home that day empty-handed. In fact, it was only on my second attempt at spearfishing the following morning that I managed to catch a fish.

You see, to actually succeed at spearfishing you need the fish to think you are part of their ecosystem. But not to see you as a threat. It’s a balance, but once you find it you’ll be able to close in and take a shot.

Once I figured this out, that’s when things started to snowball. I had a little more range after upgrading from a pole spear to a speargun, and I’d started noticing a few things around me when I was diving on the reef.

- How certain schools of fish had particular areas they frequent.

- That different times of day can change the fish you see and their behavior.

- The way you act in the water can scare the fish away, or draw them in.

It’s rare I’ll come back from a dive empty-handed these days. And I’m now the one cleaning the giant fish down by the boat ramp as the kids walk by in awe.

I’ve picked up so much knowledge from my time in the water, my only hope here is to share it with you. My thoughts on the ton of gear I’ve put to the test, along with a lifetime’s worth of tips, tricks and tactics to help teach you how to spear fish.

What spearfishing’s all about

Being underwater is the ultimate escape. There’s no better way to describe it. Slipping into a whole other world, that so few other people have seen. You’re confronted with new sounds and sensations, and everywhere you look there is life and action. Crabs scuttling over the rocks. Birds squawking for a free meal. And oh, so many fish.

Anything you’ve been stressed or worried about fades into the background and before you know it you’re at peace. Forget meditation.

But there are people who think spearfishing is a barbaric practice. Who give me disapproving looks when I’m carrying my gear. I even had one auntie chew me out after a spearfishing meet, claiming it’s people like me ruining the oceans.

She couldn’t have been further from the truth.

Every single spearo I know has the utmost respect for the ocean and everything in it. We see firsthand the impact of people on the environment we love, and many of us are big supporters of the charities and non-profits working to conserve and protect the seas.

To us, the ocean is our playground. We want it to stay pristine for our kids, and our children’s kids. They deserve the chance to learn the sport we all love.

Of course, I get that the best way to not have an impact on the ocean is to not spearfish. Because I can’t argue that taking fish out of the sea is great for the ocean. It’s not. But there needs to be a balance somewhere, and what I like to remind myself of is that it’s the least harmful and invasive of all the different styles of fishing.

With that in mind, there are a few hard and fast rules I live by when I go spearfishing.

Think of these like a code of conduct, or guiding principles that really define what spearfishing is all about. To me at least. And I’d appreciate if you stick to these too as you learn how to spear fish.

Be considerate of the ocean and environment

Despite how it sometimes seems when you’re surrounded by a big school of fish, the ocean is a delicate environment that deserves your care. Think about the impact you do have and be a little thoughtful when you’re spearfishing. Don’t shoot everything in sight, and only ever take as much fish as your family needs.

Respect your catch and the life you take

The best part about spearfishing is there is zero bycatch. You will only ever catch a particular fish that you’ve targeted, and taken a shot at. This means it’s up to you to respect protected species and know the laws and regulations on bag limits and fish sizes. I also try to avoid taking “hail mary” shots with my speargun. The last thing I want to do is miss a shot and injure a fish, only for it to escape, suffer and die at a later point. That’s not cool.

Leave no trace of your presence

The great pacific garbage patch is a real thing, and it’s important you’re not adding to the problem. Don’t ever dump waste in the ocean, and if you do happen to spot trash on a dive grab it and toss it in your boat so you can get rid of it properly. Plastic lasts a lifetime, so every piece you take out does make a difference. Oh, and don’t damage anything unnecessarily on a dive. Breaking corals is a no-no.

Give back to the community

Finally, I think it’s also important to get involved with projects that support sustainability and ocean conservation. I’ve been part of numerous projects over the years, and I make a point to donate to specific charities who love the sea as much as I do. But not just money, often your time is also valuable in raising awareness, or helping out at a grassroots level.

Even following these I’m still far from perfect, but if you’re approaching spearfishing with these points in mind, I wish you well. And so, will the rest of the spearfishing community.

Understand the different types of spearfishing

You’ve probably gathered by now that spearfishing involves getting underwater and hunting different types of sea life. But there’s a few different ways we do this.

What I do is breath-hold spearfishing. I don’t use scuba tanks to spearfish. Where I grew up it’s simply not the way spearfishing is done, and it’s also illegal. I also like to think it gives the fish a bit more of a fighting chance. So, for the rest of this guide we’re going to be referring to breath-hold spearfishing, as spearfishing. Savvy? Savvy.

Now most of the different types of spearfishing revolve around “where” you’ll be spearfishing, but it pays to know what’s what before we get too far along.

How to spear fish from the shore

Shore diving is where you’re most likely to start. Get to the beach, and swim out to any particular area that takes your fancy. The key is to look for structures, as this is usually where the fish like to hang about. I’ve spearfished in and around the pylons of jetties, along rock walls, in shallow reefs along the headland, and even along weed and sand banks.

It may not look like all that much from the surface, but there’s plenty of life underwater if you know where to look. Most of your catch from the shore will be small to mid-sized reef fish, though depending on your particular location you may get the odd pelagic cruising by.

What I love most about spearfishing from the shore is that it’s accessible to everyone. Just grab your spearfishing gear and you can be in the water hunting with the best of them.

How to spear fish from a boat

If you catch the spearfishing bug it won’t be long before you’re convincing your boat-owning friends to take you out to deeper reefs and islands you can’t reach from the shore. Or buy a boat of your own. Some of my friends paddle out much further than I’m comfortable with on a simple sea kayak to go spearfishing, and they’re constantly bringing in fantastic fish.

What you’re doing is essentially the same as spearfishing from the shore, you’re just using the boat to get to new locations that aren’t easy to access from the shore. Like an island that’s just a bit too far to swim to. Or a particularly deserted headland with no road access. The more remote it is, you’ll often find bigger and better fish there.

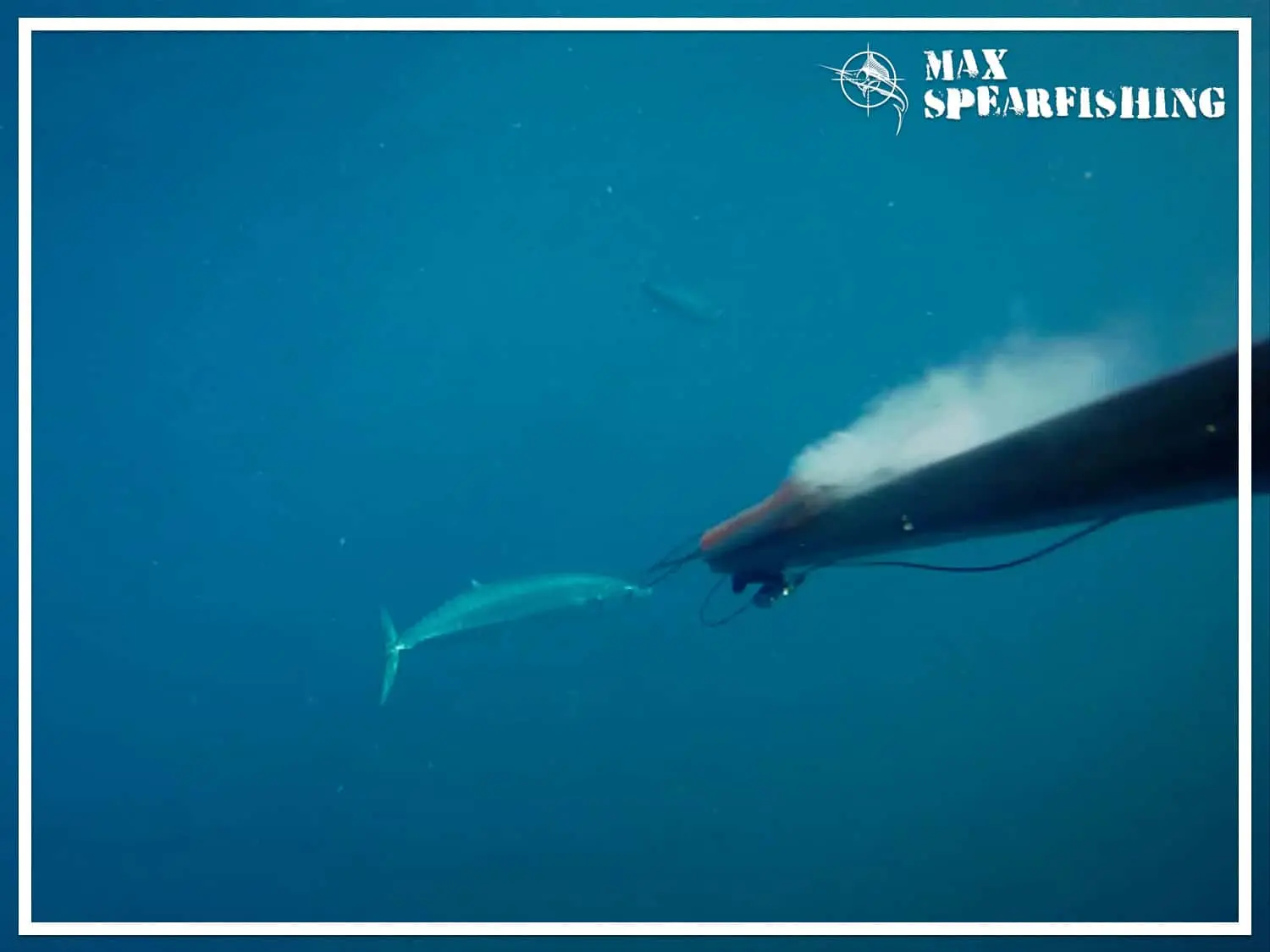

How to spear fish in blue water

Blue water spearfishing is where things get truly exciting. You’re no longer looking for reefs in shallow water. You’re out in the open ocean. Diving on some kind of structure can give you a bit of comfort at first, but normally we’re in water where the bottom is so far out of reach you can barely see it. You’re diving in deep blue water.

Then we introduce the chum. Chopping up oily bait to attract large game and trophy fish to your location. Because of the currents in the ocean you’ll usually drift along the chum lines for a few kilometers, with the boat always nearby to keep an eye on you. You’ll need keep an open eye out for sharks, they’re an ever-present danger, especially with all the bait you’re tossing into the water.

To spearfish in these areas, you will need a very large speargun designed to hunt these massive fish. Many of us will use an oversized speargun with a reinforced hardwood barrel. These “blue water” spearguns often reach 160cm or more, and have the space to use up to 4 or 5 bands. The additional length and bands add power and range to your shots, to give you a chance of actually hitting these monster fish. But that’s not the only difference.

You’ll need to setup a special kind of rigging for this type of spearfishing. It’s called a breakaway rig. We’ll cover it in detail in a separate post, but essentially its a setup where your spear is attached to a float line instead of your speargun, so if a fish you shoot takes off, it doesn’t take your speargun along with it.

How to spear fish in fresh water

You can also spearfish in fresh water, but it’s not without its own set of challenges. First though, is the legality. Many lakes and rivers do not allow spearfishing, so it’s important you understand the regulations before jumping in the water. Get a license, and be prepared for a bit of a different dive. I like to scout out some areas first if I’m diving a new location, typically you want beds of vegetation around 10-25 feet deep. The department of natural resources will have maps and information available, so do your research.

Because of the visibility, stalking your prey is pretty much out of the question. Instead, you’re going to want to add a little more weight to your belt, and simply head to a good spot and sink to the bottom and wait. The fish will come close, and that’s when you get your shot. For freshwater spearfishing you’ll be better off with a shorter speargun, I have a nice little 80cm Mares that does the job perfectly.

How to spear fish and stay safe

Now before you even start thinking about getting in the water, I need to mention safety. Spearfishing is a sport that takes place in the water, and even though I’ve been doing it my entire life, as I started pushing my limits more and more I realized how important safety is.

To stay safe in the water there’s a few things you need to keep in mind.

Spearfishing requires you to be a good swimmer

The amount of swimming you do while you’re spearfishing is intense. You’re in open water, usually far from land, and even with a boat nearby, if they lose sight of you even for just a few minutes you need to be able to rely on your ability to swim. Of course, if you’ve got your weight belt right you’ll bob on the surface, and you could always hang onto your float for a little extra boost, but you will be swimming. And swimming a lot. You need to be comfortable in the water before you start trying to learn how to spear fish.

Have a healthy respect for the ocean

On the water the conditions can change fast, and if you’ve got even the slightest feeling in your gut that it’s too rough, don’t try to go spearfishing. It’s just not worth it. The ocean is an unforgiving beast, and if you’re trying to brave big seas, it’ might just be the last thing you do. I’ve lost friends who pushed the limits just a little too far, and it’s not worth it. It’s also important to understand what’s happening around you when you’re in the water. A strong current can drag you away from your boat, or the swell surging into the headland can be a recipe for disaster. Always pay attention to what’s going on around you. Getting in and out on a shore dive is probably the most dangerous part, especially if you’re jumping in off from the rocks or hitting a spot with a strong current. Be careful when learning how to spear fish.

You will need to equalize effectively

Equalizing is one of the most important parts of learning how to spear fish. If you don’t equalize properly, the pressure in your ears can do permanent damage. Especially if you’re blocked up or trying to push your luck going spearfishing with a cold. Once you get a few feet under the water, you will need to equalize to continue to safely dive deeper. Do not ignore the pain if you’re unable to equalize and “power through it.” You can do massive damage.

Find a buddy and never dive alone

This is where most of us tend to skirt the rules, and I’m ashamed to say I’ve done it too. But it can have devastating results if you’re learning how to spear fish alone. Whenever you’re spearfishing, and staying underwater for longer and longer periods of time, you need someone watching your back. They’re your backup, and will help to keep you safe. No matter how much experience you have, find a friend and get them to come along with you on a dive. That way if you ever need help, whether it be keeping an eye on you from the boat, or if you push yourself a little too hard and black out, they’re right there to help.

Be wary of the other boats

When you’re spearfishing in the water you’re almost impossible to see. Decked out in your wetsuit, speargun, and a pair of black fins, you’d be surprised just how many close encounters you have with other boats once you start spearfishing. My advice is to invest in a diver below flag, and attach it to your float. In addition to being seen by any boaters (before you’re run down), it gives you a couple of options. First, it’s attached to your speargun which means you can let your speargun go if you happen to come across a nice lobster hole and find it easily after, or if you’re in the water with your buddy and you lose track of them. The flag helps find them. Buy a dive float and flag before you get in the water and try to learn to spear fish.

Know the dangers of the shallow water blackout

Holding your breath for longer and longer periods of time will ultimately lead to one end. The shallow water blackout. We push ourselves to the point of oxygen deprivation, and it’s inevitable you’ll eventually push it too far. I’ve blacked out underwater, and it’s a surreal experience. Without swift action from my buddy, I would have drowned. If your dive buddy blacks out, you need to get them to the surface and keep their neck supported until they come around. You may also need to perform CPR. It’s scary, but it pays to be prepared for everything before you start learning how to spear fish in the ocean.

Be aware of the ocean’s biggest predator

I shouldn’t have to tell you this, but in the ocean you’re no longer on the top of the food chain. Sharks have that spot. And they’ve got no hesitation coming in and relieving you of your catch. Where I grew up on the coast the waters were particularly sharkey, and it was a hard-and-fast rule to never keep your fish on you. Clipping your stringer to your belt is a good way to lose a chunk of your torso if a shark comes in for a taste. Instead, we’d clip our catch onto a stringer on our float line. It’s still within easy reach, but means you’re far enough away while you’re learning to spear fish that you’re not in immediate danger if a shark comes in.

Never point your speargun at anyone

Much like a firearm, a loaded speargun can be a deadly weapon and there’s no shortage of gory shots where spears have gone wrong. They’re all over social media. You don’t want to be speared (or spear someone else for that matter) with your speargun. Especially if you’ve mounted a camera to your gun. Do not point your speargun at your dive buddy, even if you’re planning to just film them. Things go wrong, and you don’t want to be racing to the emergency room because you misfired your speargun. Never point it at anyone.

With every sport there’s risks, but the real key is simply understanding these, and ensuring you take steps to mitigate each as you learn to spear fish. That’s when you start spearfishing smart.

What you need to get started spearfishing

The amount of gear you need to go spearfishing can seem a little overwhelming. Not only are there a ton of different brands and types of gear, you’re not really sure what’s best for the type of spearfishing you’ll be doing.

My advice, is to not overthink it.

I started learning how to spear fish with a pole spear, a mask and snorkel from a cheap dive kit, and a pair of rubber fins. That was it. And I was in the water, catching fish day after day. But I wasn’t all that comfortable, especially when the water temperatures dropped.

There are a few things that you could purchase that would make your life a little easier as you learn to spear fish. And I’ve got good news too. Once you’ve got your gear sorted, there’s very few “on-going” costs when it comes to spearfishing. You just need to get to the water and get in.

In short, you’re going to need these:

- Speargun

- Fins and pockets

- Snorkel and mask

- Wetsuit

- Gloves

- Dive knife

- Float line and stringer

- Weight belt

Speargun

To go spearfishing you need a tool to catch the fish. A speargun is what most people use, but many beginners start out with a pole spear.

There are two types of speargun.

Pneumatic and band-powered. But as most beginners start with a band-powered speargun, it’s also the most common. You’ll see a handle grip with a safety switch and trigger. A long barrel that extends to the muzzle. A metal spear that clicks into the trigger mechanism near the handle, and the rubber bands that stretch back and “arm” the speargun once they’re secured in the notches in the spear. The sharp end of the spear is the tip and the barb, and the spear attaches to the base of your speargun with a length of line.

Just how powerful your speargun is will determine the range you get with each shot. It’s also an important factor in choosing the right speargun for where you’ll be spearfishing. If you’re in low visibility, looking in ledges and caves for fish you’ll want a shorter gun (65 to 70cm). This will minimize any damage you do to your gear from damaging the shaft on the rocks. If you’re diving in deep blue water, most spearfishermen will use large guns that are 140 to 160cm +, with multiple rubbers for even more power.

In general, I recommend finding a balance somewhere in the middle, and getting a general reef speargun that’s 100 to 120cm.

Fins

A good pair of spearfishing fins will help you easily dive down to hunting depth, using the least amount of energy possible. Efficiency is critical, because the more energy you burn as you kick, the faster your air will run out. Which means you need to ensure you get the right fit with your spearfishing fins.

Too tight, and you’ll get cramps in the arch of your foot while you’re diving.

Too loose and you’ll lose power in your kicks, get blisters where the boot rubs, and potentially even lose your fins entirely if they slip off in the water.

Just remember you’ll probably also be wearing a pair of neoprene socks, so ensure you’ve got enough room in the boot when trying them on in the store.

The cheapest fins are plastic polymers, then you’ve got the fiberglass blade models, and if you’re looking for a top of the line pair of spearfishing fins, you could always opt for carbon fiber. My advice would be to get a pair fins with soft to medium “stiffness” in the blades, as they’ll be easier for beginners who aren’t strong swimmers.

Snorkel and mask

Your snorkel and mask serves an important purpose. It allows you to breathe on the surface while scanning for a hunting ground, and allows you to actually see underwater.

Again, it’s important to find a mask that fits comfortable on your face, but what you’re looking for here is the seal. In other words, how well it suctions on to your face. Otherwise it’s going to leak as soon as you get in the water.

The best way to choose the right mask is to head down to your local dive store and try on a bunch of different models. Just press it to your face (without putting the strap on), and a slight inhale through your nose should pull the mask tight. You know it’s a good fit if you’re able to lean forward and the mask doesn’t fall off.

Wetsuit

If you want to have any hope at staying calm and relaxed underwater, you need to be comfortable. And that’s what your wetsuit is for. To keep you from getting cold.

A wetsuit is a relatively straightforward piece of gear. It’s a neoprene rubber “bodysuit” that allows only a tiny bit of water to enter the gap between your skin and the suit. The water quickly heats up, and for the most part, stays trapped within the wetsuit so you’re able to stay much warmer.

Generally, I’d recommend a 3mm or 5mm wetsuit for most climates, though if you’re somewhere quite cold a thicker one would be advised. Normally spearfishing wetsuits come in two pieces, and use what’s known as open cell technology. It’s a specific type of rubber that’s both comfortable and soft, though they can be a bit tricky to get into. It’s very important you get your measurements right when buying a wetsuit, as they need to be a snug fit. Too loose and you lose all insulation. Too tight and it’s impossible to get on and off.

Gloves

Once you’ve got your wetsuit sorted you’ll need a pair of gloves. They keep your hands warm, but also add a layer of protection from any sharp spines or edges on your fish, jagged rocks and barnacles, or any crayfish you’re trying to grab. What you want to look for here is reinforced palms and fingertips (in my experience it’s been the pads of the fingers that wear out first), that fit well without being too tight.

Dive knife

When you’re in the open ocean anything can happen, and having a blade is a smart idea. I use mine to quickly dispatch any fish I catch. Because a struggling and injured fish is a much bigger shark attractant than a little blood in the water. And not just this, if you’re ever in an emergency situation, having a knife could just save your life. If you’re underwater tangled in old fishing line you could cut yourself free, and of course you can always use it to chum up a few baitfish to attract some larger prey.

Float line and stringer

Going spearfishing without a float and stringer is a recipe for disaster. Not only does it show any boats in the area you’re spearfishing, it gives you a safe place to secure your stringer and any fish you do catch. My float-line attaches to my speargun, which also means I’m able to “let go” should I happen to come across a large fish, or have my shaft get stuck in a cave or let a fish wedge itself into a crevice. It’s saved my speargun on more than one occasion.

Weight belt

To offset the buoyance of your wetsuit, you need a weight belt. Now you’re going to need to do a few calculations, as there are a few things that will affect the weight to use.

The first is your body. Your height, size and shape. The thickness of your wetsuit will also have an impact. My advice is to start with a little less weight than you think, and add weight on following dives. What you’re looking for is to float on the surface, even after you exhale, but you become neutrally buoyant somewhere between 5 and 10 meters.

For me, at 84kg, I use 7kg of weights along with my 5.5mm wetsuit.

As a general rule, take the thickness of your wetsuit + 2 to calculate the weight you need.

- A 3mm wetsuit = 3 + 2 = 5kg of weight

- A 5mm wetsuit = 5 + 2 = 7kg of weight

Just remember. You need to be able to drop the weights in an emergency, so look for a weight belt with a quick release buckle. If you blackout or need to get to the surface fast dropping your weights will help to get you to safety.

Rigging your spearfishing gear for your first dive

At this stage of the guide I’m going to make a few assumptions. You’ve eagerly bought all of your spearfishing gear, and you’re looking at it like you don’t know what the heck to do with it all.

That’s fine. In this section we’re going to cover some important steps to ensure the first time you get in the water to learn how to spear fish it’s a good one.

De-fogging your snorkel the first time

Taking your brand-new mask out of the box it looks like a million dollars.

But there’s something to do before you get in the water. You see, when the mask was made in the factory the glass picked up a ton of chemical residue in the process. If you forget this step the first time you step in the water your mask will fog up like crazy. What we’re going to do now is what’s known as “pre-treating” the mask before your first dive.

Some people swear by a technique using a cigarette lighter. Get a good flame, and pass it over the glass to “burn” off any residue that remains. To me, that’s a little scary, as you could also damage the delicate rubber seals in the process. I recommend using toothpaste.

Yes. Toothpaste.

Raid your bathroom for some plain old fluoride toothpaste. Squeeze a decent amount onto your fingers and rub it into both sides of the glass with enthusiasm. You’re going to want to spend about 20 to 30 seconds doing this. Then rinse it all off with water. And repeat. Do the process about 5 or 6 times, an you’re good to go.

Oh, I’d also recommend buying a small tube of anti-fog, which you can put in right before your dive. Or shampoo also works. Just a couple of drops in each lens, then rinse it off quickly and you’ll be able to dive with no fog problems. Trust me. You don’t want this.

Check your speargun is ready to go

The first time using your speargun there are a few things to have a look at. Especially if you’ve ordered it online and haven’t yet had a chance to take it in the water.

First, is the trigger and the mechanism. Try flicking the safety on and off, and see if you’re able to pull the shaft from the speargun by hand. What you’re testing here is how well the “lock” inside the trigger is functioning, and ensuring that when the speargun is under pressure there’s little chance for a misfire.

Next, have a look at your shaft. It should be perfectly straight, which you can test by rolling it along a flat surface, like a concrete floor in your garage, or on the top of a table. There shouldn’t be any noticeable warps or bends in the shaft. It’s new.

Now, you want to make sure the connection between your shaft and the speargun is sound. Take a look at how the line has been tied, and if it looks a little suspect it doesn’t take much to cut and replace this with a new line. You should be right, but it’s worth checking.

Then, the spear tip. I recommend getting a shaft with an interchangeable tip, so you can screw and change these out as you damage them. It does happen, especially if you’re new to spearfishing. Your tip should already be sharpened, whether it’s a pencil tip or a three-sided point, but if it feels a little blunt you can always take a metal file to it and sharpen it up.

I’ve also had a couple of tips be “loose” in the water, so test screwing yours on and make sure it can sit tight. If not, a couple of rounds of plumbers tape on the spear tips thread before you screw the tip on next should ensure it fixes on tight.

Finally, have a look at the rubbers. There shouldn’t be any visible signs of wear on the bands themselves, you should be able to slide these around inside of the muzzle to check along the entire length. Also take a look at the ends where the metal wishbone is attached, these are usually tied on with cord, they should be nice and tight, with no signs of wear either.

Oh, and depending on the make and model of your speargun, I’d also recommend attaching a simple clip to connect your speargun to your float line. I use one of these to clip my float-line on, and it’s fantastic.

Tick all those boxes and your speargun should be good to go.

Attach a float line and stringer

Right, now you need to setup your float line. You’ve got the float you ordered and a stringer and a dive flag, and you just need to tie these all together. The float should have a space to put the flag, and I like to just hang the stringer underneath. Then I’ve got a length of line which attaches in to the clip on the handle of my speargun.

It’s probably 30 meters long, which is plenty long enough for most of the diving I do. I only ever swap this out for a longer one if I’m going deep water spearfishing, then I change over to a breakaway rigging setup too. Make sure all of your knots are tight, the last thing you want to do is let go of your gun and find that it wasn’t properly secured.

Do I need a speargun reel?

If you’re at this point you’ve probably come across the different setups for reels versus the line guns. Probably the main difference when you’ve got a reel attached is you’re no longer feeling a “pull” on your gun from your float-line.

It also means you’ve got one less thing to worry about, especially if you’re spearfishing from the shore and there’s a chance your float-line will get tangled in the rocks and reef. Some of my friends swear by their reels as they use a different setup (they simply hold onto their gun and reel instead of using the float-line), but for me I prefer the connection to the surface a float line gives.

Rules and regulations to keep in mind

There are plenty of regulations surrounding the sport of spearfishing. Fishing is a highly regulated industry, and in many states, you will require a license to do the sport. But not only that, there’s also rules on where you can and cannot spearfish, as well as certain seasons, size limits and protected species you must obey.

As an example.

In Australia, if you’re spearfishing in New South Wales you need a fishing license, and it’s prohibited to use scuba gear, or even a flashlight to aid you when spearfishing. In addition, there’s strict enforcement of bag limits, sizes and catches, and a host of marine sanctuary zones you need to abide by.

In the United States, different states have different rules. Florida is notably strict on the areas you can go spearfishing, requiring those spearfishing to typically be several hundred yards offshore. California has a host of marine protected areas, protected species, and size and bag limits. Differently though, you’re allowed to use scuba gear while spearfishing.

Every country and state has different guidelines for spearfishing. It’s important you do your research and understand the rules and regulations that apply for the area you’re spearfishing in. Large fines, even if you’ve made an honest mistake, are the last thing you want. The officers won’t care.

So, go to Google and search. Look for information on the department of fisheries websites. They’ll also usually have maps available and a ton of information on identifying different species of fish, bag and size limits, as well as where you can go spearfishing. Do your due diligence, and learn the rules, so you can stick to them as you start learning how to spear fish.

What to expect your first-time spearfishing

Spearfishing is kind of like snorkeling at first. You’ve got much the same gear, you’re kicking around in the water, and searching out fish to look at. Of course, you’ve got a speargun now and you’re looking for your dinner, but that’s not the most important point.

Relax, and don’t forget to enjoy yourself.

Your first day in the water is going to be a kaleidoscope of energy and emotion. Don’t get too caught up on trying to spear fish, or pushing yourself to stay underwater for too long. Just enjoy yourself. Explore the world under the sea, and focus on your practice shots, diving underwater, and getting comfortable with all of your new spearfishing gear. It can take time to learn how to spear fish consistently, so don’t stress out.

Choosing a spearfishing spot

Finding good spearfishing spots is a bit of an art form in itself. My advice, would be to start with an area that’s protected from both the winds, and massive swell. In the leeward side of a headland or reef, or perhaps a pier or jetty you can explore. Look at the weather in your location, and use Google Maps to find a somewhat protected spot. The calmer the better for you as you learn to spear fish.

You could even go down to your local fishing tackle store. They’ll be able to give you advice on where to go and what you’re allowed to hunt. And may even have some of the rules and regulations about spearfishing (in brochure form) that you can take with you.

Right. There’s three things I look for when I dive.

- A steep drop off or deeper water. It brings bigger fish closer.

- The potential for good tidal and current flows, which brings fish in to feed.

- Any structures or natural formations for the fish to hide and shelter in.

Of course, it’s also important you’re able to actually get to the spearfishing spots you’ve found. Often what looks like a good site on the maps is actually impossible to get to unless you want to abseil down a cliff. Be sensible here people, and find easy entry points.

Getting in and out of your wetsuit

Getting into a spearfishing wetsuit can be a bit of an ordeal, especially the first time you’re doing it. It’s the most awkward part of the whole process.

What I will say is that it’s going to be impossible without some kind of lubricant. You use it to coat the inside of the wetsuit before trying to slip it on, so you can get into it easily without tearing the neoprene, or stripping your legs of every hair you’ve got.

Generally, I use a mix of conditioner and water as my lubricant. Anything else and you run the risk of getting a rash throughout the dive, as it’s too “soapy” and will dry and irritate your skin. I’ve got a small bottle of conditioner I always take with me, and if I remember I’ll mix up a bottle with a couple of squirts of conditioner and water before I go dive.

Oh, and during the winter using warm water for your lube is fantastic.

Start by squirting the mixture into the pants first. I hold the feet tightly closed with one hand and give it a good slosh around to ensure the inside is fully coated. I then tip whatever’s left into the jacket.

Once it’s well lubricated, slide your legs one at a time into the pants, pulling it all the way up and bringing the shoulder straps up and over. Add a little more lube to the jacket, and slide your arms in up to the elbows. Holding it open at the waist, raise your arms over your head and then bring them down, it should all just slide into place. Shimmy the jacket down, and secure the beaver tail in place between your legs.

Getting out of it is essentially the same process in reverse. With a bit more shimmying.

Getting into the water

You’ve got your spearfishing gear and you know where you’re headed. But before you start running down to the water, it’s important to have a bit of a plan in mind.

The trick to entering any piece of ocean is to be patient. Spend a couple of minutes observing the water, the sets of waves rolling in, and choose the right entry point.

When you’re learning how to spear fish from the shore you’ll need to make it through the waves and breakers to get to the reef. One of the surest ways to lose all of your gear is to waddle out through the breakers or slip on the rocks and drop it all.

I know. I’ve slipped on the rocks more than I’d care to admit, and have even lost a bootie in the process. My advice is to get as ready as possible before you getting in the water.

For me, this means I’ve done the following.

- Wetsuit and weight belt on, along with my gloves and booties.

- My mask gets a couple of fresh drops of shampoo to stop it fogging and I rinse this as soon as I get to the water and put it on properly

- My dive knife is strapped onto my arm along with my dive watch

- I wrap my towline around my float so it’s not dangling everywhere and clip it to my speargun

- I carry my float, towline and speargun in my right hand

- I carry my fins in my left

It’s a bit awkward till you’re in the water and you can put on your fins, slide your mask down, and grab hold of your speargun and start swimming out of the waves.

Off the beach, I’ll put my fins on when I get to about waist deep water where it’s deep enough to swim. But off the rocks it’s just as easy to slip these on before I step in, kind of like how you do when you’re scuba diving. Just make sure you’re jumping into water that’s deep enough, and be very careful if you’ve got fiberglass or carbon fiber fins. You may want to save putting these on till you get well-away from the rocks.

Getting out of the water

Now here’s where things get interesting. You need to have a good idea of how you’re going to get out of the water, before you get in. Plan, now, so you’ve got options should something go wrong, or the conditions change when you’re in the water.

I usually look for two or three good spots to exit from, when I’m diving a new spot. One that’s as close as possible to where I’ll be diving, a backup that’s maybe 500m or so away in case I underestimated the current, and also do a quick scout of the beach in case I can simply swim in. Just remember to time it right, so you’re not right in the middle of the breakers when that set of waves rolls through.

How to load your speargun

After you’ve decided where you’re going to get in and get out, and you’ve made it into the water and swum out through any breakers, it’s time to get serious. It’s time to learn how to spear fish.

But first, you need to load your speargun.

And the first time you do it, it can be a challenge. I’m assuming you’ve done some research on the proper technique, or had a friend (or the clerk at your local dive shop show you how to do it). Perhaps you’ve even had a go at pulling the rubbers back without being in the water. That’s fine, just don’t click them into place. I usually do this when I’m shortening my bands, to ensure I can still load it when I get it out in the water.

Let me say this again. Do not, EVER, load your speargun out of the water. And NEVER at any point, should you shoot it out of the water. It will hit the end of your line, and it will come sling-shotting back towards your head faster than you can possibly imagine.

Here’s how to load your gun using the “chest-pull” technique (the only one I recommend):

- Grab the handle of your speargun in your left hand and the rubber with your right. It helps if you’re wearing a wetsuit, and you’ve got a pair of spearfishing gloves.

- Make sure the safety is switched ON, and that there is no one in the water directly in front of you.

- Wedge the handle of the gun in against your chest (some spearguns even have a “butt” that makes this more comfortable), and use your left arm to position it in place.

- Once it’s in place, hold the gun tight and move your left hand up to the rubber, so you’ve now got (a) the butt of the gun against your chest, and (b) one hand on either side of the rubber ready to stretch it into place.

- Push out with your chest, while simultaneously pulling in with your arms, bringing the wishbone down into the notch where it fits into the spear’s shaft.

- Click the metal wishbone (or cable) into place and repeat the process again if you’ve a second rubber to load.

Once you’re done the gun is loaded, so I’d be careful where you’re pointing it. Spearguns (though these are mostly the cheap ones that the trigger mechanism has failed on) have been known to discharge without pulling the trigger. It’s rare. But be sensible. Don’t point your speargun at anyone, just in case.

Now just switch off your safety when you’ve found a target fish and want to take a shot.

Finding a hunting ground

Once you’re in the water, the hunting begins. But first, you need to find the fish. I like to casually swim along the rocks or whatever structure you were aiming for, while keeping an open eye out for any fish activity. You need to pay attention here, as there are so many external factors that will affect where the fish actually are.

The tides. The current. The visibility.

But what I want to make clear here is one thing. You don’t need to push out to the deepest water to find the best fish. Fish will school and hang about the areas where the food is. Often, this is the intertidal waters that are less than 3 meters deep. The key is to be stealthy, and not make big, jerky movements that will alert the fish to your presence, and scare them away. Be calm and collected in your movements, and keep an open eye out for any targets.

Of course, this all gets easier with time and experience as you learn how to spear fish. Especially at your local spots where you’ll soon “get to know” where certain types of fish like to hang about. I call these landmarks, and it’s important to remember where each spot is, so you can find it again next time.

There’s a few ways I do it.

The pathfinder.

One of the reefs I regularly dive has become such a second home to me that I’ve almost got a route mapped out, before I get into the water. I follow a certain line of rocks along a sandbar till I hit a massive peak (it juts out of the water in the middle of the reef), then swing out wide to the left to cross a number of gutters and channels. Following the same path each time I dive here ensures I always hit my favorite spots for game fish, and load up my bag with lobsters.

The secret spot.

With any luck you’ll come across a few of these as you start spearfishing more and more, the trouble is, how to find this exact spot again next time? Of course, the GPS in your boat can be a big help, but if you’re shore diving you’ll have to learn how to take your own bearing. The simplest way is to find a prominent feature on the shoreline, and line it up with something in the distance. I line up two. A set of rocks at the end of the beach, with another headland (so I know I’m on the right line), and a path down to the beach and a bright blue doorway on a house by the water. These two bearings are 90 degrees apart, which makes it a good cross reference. Where these two lines intersect is the best jewfish hole I’ve ever found on my reef, but if you didn’t know it was there you’d struggle to find it.

How to break the surface with the perfect duck dive

Executing the perfect duck dive is important for two reasons.

- Get it right and you’ll slip under the water with zero effort.

- Get it right and you’ll not burn any excess oxygen getting to depth.

There’s a knack to duck-diving, and it takes a little practice to get right. Much like learning how to spear fish, it’s practice you need to improve. Because I spearfish with a snorkel in, I’m going to assume you’re on the surface, facing down into the water.

Here’s what you do.

- Take your final breath at the surface, and remove your snorkel

- I keep my speargun in my right, and use my left hand to swim and equalize

- Grab your nose with your left hand to “equalize” first, before you start to dive

- Stretch your arms in front and aim your body down

- Bend forward at your waist, while keeping your legs straight

- Raise both legs out of the water, so they point straight up

- The weight of your legs will push you under

- As you go down, bring your left arm to your side in a breast-stroke movement

- Bring your left hand up to equalize again, and leave it there

- Once your fins are in the water, start kicking to push deeper, equalizing as you go

- Remember to kick strong the first few kicks to use momentum to get depth

Now of course, it’s going to take you a little bit of practice to actually get the hang of this, all I can tell you is to keep at it. It does get easier as your spearfishing skills improve. Your focus should only be on getting your duck dive as smooth and efficient as possible, so you’re hitting the bottom with as much air in your lungs as possible.

The importance of proper equalization

One of the most critical steps in learning how to spear fish is learning to equalize your ears. If you don’t get it right you can injure your ears, which leads to discomfort, pain, and even make you feel like there is water still trapped in your ears after a day spearfishing. My advice is to equalize more. I used to only do it when I felt the pressure building, but after taking a freediving course I learnt a trick. Equalize on every other kick as you descend.

It’s very important you equalize as you dive because of the pressure you experience as you dive deeper underwater.

Within your ears are small pockets of air, and these are compressed as you dive. If you don’t balance out the pressure you will feel pain, which can even lead to serious injury if you try to “push through it.” Eventually the capillaries in your sinuses will burst, and you’ll get a nosebleed. This is a big sign that something is seriously wrong.

And it’s also why it’s important to never go spearfishing if you’ve got a cold or the flu. When your nasal cavity is blocked, your ability to equalize is usually removed, as the congestion has all your sinuses blocked up. So, air can’t pass through, and you can’t equalize.

Now there’s two different techniques to equalize. Both work on the same principle, the difference is where the air comes from.

- Valsalva uses the air in your lungs to equalize

- Frenzel uses the air in your mouth to equalize

Of the two, most people will do Valsalva naturally. The trouble is, this isn’t the most efficient way to equalize, and you will struggle to properly clear your ears once you start diving at any significant depth. To find out how you equalize, you can do a simple test.

Place one hand on your stomach, and use the other to block your nose. And then equalize. If you feel any movement in your abdomen, anything at all, that’s because you’re using your diaphragm to push the air into your windpipe to equalize, and you’re doing the Valsalva technique. You have to train yourself out of it.

It’s not particularly easy, but once you learn how your spearfishing will improve.

- First, you need to yawn.

- Now flatten your tongue.

- Feel the muscle pushing it down? Good.

- Your ears may even “click” when you do this. That’s very good.

- Relax for a second or two.

- Now put your tongue back in the flat position.

- Breathe in and out slightly through your nose.

- You should hear it echo in your ears.

- Keep your tongue in the flat position.

- Now pinch your nose and breathe out the same way.

- Your ears will equalize.

- There may even be a small sound. That’s good.

From here on out, you just need to flatten your tongue, pinch your nose, and breathe out to successfully equalize. Once you start practicing this Frenzel technique you’ll get much better at equalizing. It’s the most effective way to do it. Just remember. If you’re spearfishing and something in your ears hurts, it’s your body’s way of telling you that something isn’t right. Get back to the surface, and call it a day. Better to sit out for a few days than cause serious damage to your ears.

How to actually sneak up on a fish

Once you’ve duck dived and finned your way to the bottom, equalizing as you go, it’s time to start hunting your prey. The fish.

There are a few good ways you can do this. Just remember. Any quick, sudden movements are guaranteed to scare off any fish in the area. It makes a big difference to move slowly, and never approach a target fish directly. The key is to not be actively aggressive in the water as you learn how to spear fish. Focus on your breath hold, exploring, and remaining calm.

Let the fish come to you.

Of course, there are a few different spearfishing techniques you can use as you learn to spear fish.

The first is to stay still. Power to the bottom and grab hold of a rock or something to stay still. Fish are naturally inquisitive, and if you remain in place, without and jerky movements for at least ten seconds, I can guarantee you they will come up and take a look at you.

I also rather like the ambush. Find a ledge, a rock wall, or a shelf to position yourself behind, and use the cover to sneak up on your prey. You will need to be stealthy, and be ready to take your shot quickly before the fish dart off once your presence is known.

If you’re in an area that needs exploring, you can use the crawl. Instead of kicking and creating a big fuss, use your free hand to pull yourself along the bottom so you can cover more ground. This technique is great if you’re after fish hiding in caves, or lobsters too.

Depending on the fish in your area, you may also be able to bait them in.

Tossing up handfuls of sand can draw interest, along with strumming the bands on your gun, or tapping a rock or a piece of dead coral onto the reef. You can also use chum to draw in larger, predatory fish. In open water, using lures and flashers can draw in big pelagics.

Lining up for the perfect shot

When you’ve found the right fish and you’re ready to shoot, don’t forget the importance of maintaining a slow steady speed. Go too fast and you’ll spook the fish. Bring your speargun up to bear, and get as close to the fish as possible. In general, you should be able to get within two to three feet of them, depending on just how skittish they are.

If it’s your first time spearfishing it may be worth setting up a bit of seaweed or something in the water you can use as a target. To get a feel for how your speargun actually shoots. I get it can be tiring to spend the first part of your dive doing 10 to 20 practice shots, but it’s important you understand how to aim it correctly if you want to learn how to spear fish successfully.

Because your goal is to aim for a tiny part of the fish.

You want to hit the point on the fish where the backbone connects to the head. Land it right and you’ll kill them the second your spear impacts. This is known as “stoning” the fish, and gives it a fast death that’s as humanely as possible. Of course, it’s not possible to hit perfectly with every fish, and if the fish is still alive simply bring it up to the surface, dispatch it quickly with your knife, and unthread it from your spear and onto your stringer. It’s important to kill your fish quickly, as an injured, struggling fish is a much bigger shark attractant than a little blood in the water.

Just remember to make every shot count. You don’t want to injure any fish unnecessarily, and don’t take wild “hail mary” shots on the off-chance you’ll land it. The last thing you want to do is hurt a fish and have it tear itself from your spear, only to die from its injuries later in the day. That’s simply a waste.

But how much range do I have?

Talk to five different spearo’s and you’ll get five different answers. Ultimately, it will come down to the speargun you’ve bought, the rubber thickness and length, and also how hydrodynamic the shaft is.

It’ll also depend on the fish you’re targeting. Generally, your maximum range is about 2 to 3 meters, any further and you risk the fish getting startled and moving out of the way. Of course, it’s much easier to hit a big fish than a smaller fish, which is why it then becomes very important to buy the right speargun for the conditions you’ll be learning how to spear fish in.

What to do with a fish on my spear?

Once you’ve successfully speared your first fish that’s awesome! Congratulations. Now you need to reel it in. Pull carefully on the line, and bring the fish back to you. Don’t rush, and avoid making any jerky movements as you can tear the prongs through the fishes body, and you’ll lose it. Be gentle and firm.

Once I’ve got the fish in close, I use my right hand to grab the shaft, and with my left take hold of the fish. Then with my knife I’ll quickly dispatch the fish, with a cut upwards from the gills and through the backbone.

The only cautionary words I have here are to be careful with bigger fish, or any species that like to swim down into a cave once they’ve been shot and tangle your line.

You don’t want to get dragged down, which is also precisely why my speargun clips onto my floatline. I can let go at any time without concern of losing my speargun, or the fish. Then after a few quick breaths on the surface I can dive back down to the bottom again and figure out the mess.

I thread the fish onto my stringer, and then it’s time to reload and go again.

But what if you’re struggling to even load your speargun?

It may be that you’re using the wrong technique (like hip loading instead of chest loading), or it could also be that you’ve got rubbers on your speargun that are a little too short. You could always lengthen these a touch just until you get used to spearfishing, and then swap back to the shorter ones after you’ve nailed your loading technique. Don’t fret. It takes a little time to get comfortable in the water as you learn how to spear fish.

On my first speargun I actually swapped out the single 20mm band for 2 x 16mm rubbers when I was just a kid, as they made it much easier to load, while still giving me a decent amount of power from the speargun.

Caring for all of this spearfishing equipment

Once you’ve invested a few hundred dollars in the sport, it falls on your shoulders to take the best possible care of your spearfishing gear. I’ve had spearguns that have lasted reliably for years and years, because I was always fastidious in keeping them clean.

It’s critical.

Because salt water is one of the evilest things on the planet.

It gets everywhere. And combined with a little sand, it can do a massive amount of damage to sensitive parts of your gear, like drying out the rubber foot pockets on your fins, sending the silicone surrounding your mask cracking, and that’s not all. Dried salt water leaves all the salt behind, which is the perfect accelerant for rust.

You do not want your trigger mechanism rusting up. You do not want any of the nice, shiny metal parts of your speargun corroding and disintegrating.

I use a two-step process to clean my gear.

The first is fresh water.

Every time I return home from spearfishing, before I come inside or start filleting and cleaning any of my fish, I take care of my gear.

My wetsuit, mask and anything small (like my knife, dive watch, and booties) get dumped in a tub of fresh water to soak for a sec.

Using a hose, I pull my speargun apart completely (take the shaft out, unscrew the tip, and give everything a good hose off. Make sure to flush a lot of water in through the trigger.

I pull everything out of the tub, and give that a good hose off too. Then it gets hung to air dry in a shady spot in my yard.

But there’s a few rules.

- Don’t leave your gear in direct sunlight, it’ll age all the rubber faster

- Don’t leave it outside where anyone can see it, and steal it from your yard

- Stand or hang up your gear so it dries properly (don’t just leave it on the ground)

Every now and then I’ll use a little oil or grease to keep all the mechanisms inside my speargun in good working order, especially in the trigger, and I keep an open eye on my rubbers as these do need to be changed every few months if you’re diving a lot. Oh, and if you’ve got a nice wooden gun, a little oil on the barrel every now and then will help it to lock out any moisture and stay looking like a million bucks.

Taking care of your gear is truly smart, as it’ll ensure your speargun will last more than a season or two. And that’s important, especially when you start dropping hundreds (or thousands) of dollars on top-of-the-line gear.

How to swap out the rubbers on your speargun

Depending on the setup of your speargun, eventually you’re going to need to change the bands. I’d recommend taking it out for a dive or two first, especially if you’re new to the sport, just to get a “feel” for what it’s like to load in the water before you start thinking about shortening (or lengthening) what you’ve got.

Of course, you can buy ready-made bands from most spearfishing shops, but I prefer to tie my own. It’s not all that difficult. And it’s something I recommend you do at least a couple of times a year if you’re spearfishing frequently (or as soon as you notice any wear on your bands).

Here’s how I do it.

- Cut through the old bands and remove these from my speargun.

- Carefully slice through the cord that locks the wishbone in place.

- Measure the length for the new band from a piece of rubber.

- Add a drop of conditioner to the hole in the end, on both sides of the rubber

- Push the “ball” on the end of the wishbone inside the rubber band

- I usually position it so that it goes about half to three-quarters of an inch deep

- Take a length of cord (the dive shop will sell this too), about 25cm in length

- Make a clove hitch knot (below the ball) and pull it tight.

- I lock one end in the vice on my bench and pull the other with a pair of pliers

- Just be careful you don’t pull it too tight the cord cuts the rubber

- Add two more half-hitches for good measure

- Cut the cord so there’s about 1cm left hanging

- Melt the ends of the cord with a flame to prevent any fraying

- Repeat on the other side.

It seems like a hassle the first time you change your rubbers, but with the right gear and once you get the hang of it – it’s really just a 10-minute job to swap these out. Keep an eye on your bands as you’re learning how to spear fish, and once they start to wear, it may be a good idea to change them.

The benefits of joining a spearfishing community

If you’ve got a local spearfishing club in your area, I highly advise joining.

Not only will you meet new people who share the same passion for the sport, it gives you the chance to learn how to spear fish from others who have far more experience than you. You’ll pick up spearfishing techniques far quicker, and they may even have training sessions to bring you up to speed on breath-hold techniques and safety courses that are far better to practice in-person, then doing it alone after you’ve read about it on the internet.

The clubs near me are always hosting dive meets, competitions and events, and work hard at building a community of people who truly love spearfishing. It’s fantastic.

Plus, you never know who you’ll connect with. Make friends with someone who already has a boat and suddenly you’ve got the opportunity to get out into deeper water, and learn how to spear some much bigger fish. And that’s awesome.

Go get in the water and have a good time

Right. So, by now you should have an idea of everything you need to learn how to spear fish, gear up, get in the water, and have a good time spearfishing. It can seem like there’s a whole lot to it, but just remember. It’s up to you. What you want to get out of the sport. I spent my first years with just a pair of flippers, a pole spear, and a mask, and I had a ball. The trick is to just get out there, and start exploring the ocean. You’ll have a good time.

Happy spearin’

Max Kelley